I’ve been increasingly tweeting about the “transformation” of our civic institutions necessary for them to survive in the 21st century, but what that really means is a bit hard to explain. I want to talk about a prototype I built over a weekend last October when trying to figure it out in my own head, in the hope that it helps.

I built it with the Labour Party in mind. I had recently left working on the digital transformation project and, almost as a bit of therapy for myself, I wanted to release a load of things in my head into some code. But in doing so, I think it touches on some of the challenges that any organisation that wants to be member led and/or heavily relies on volunteers, which makes up a large percentage of our civic institutions.

This is going to be an oversimplification, but we’re dealing in abstracts, so forgive me. The majority of successful digital products in existence today are built on two possible organisational models: atomised individuals interacting with each other, or a centralised organisation (typically a company) interacting with its users (typically customers).

There are probably many reasons for this, economic and political, but this is where we are. Any organisations that want to use these tools are forced into choosing between something like Whatsapp, which quickly allows atomised individuals to communicate with each other, or a traditional CRM which encourages the organisation into a more staff/customer model.

You can see this forced dichotomy playing out in the language of this sector; you have ‘traditional organisations’ trying (and mostly failing) to engage with the ‘grassroots’. Both have their advantages and disadvantages, but neither are particularly effective in 2017.

Traditional organisations are pulled into creating bureaucracies that are better suited to a corporate company of the 1990s. ‘Volunteers’ suddenly have to behave more like staff members, while new members who are unable or not yet willing to make such commitments begin to see the organisation as a professionalised company to be a customer of, rather than an active member.

Meanwhile, grassroots organisations struggle to create any useful bureaucracies at all, rapidly collapsing under their own weight if they try to expand or build power. They are too risky for power to engage with seriously. Without simple, public ways for new members to get involved, they often end up cliquey.

I feel there is the possibility to build new bureaucracies, largely written in open source code instead of rulebooks (because it’s 2017), that break down this dichotomy, and allow smaller grass roots teams to help and be helped by the more centralised and professionalised HQ. This prototype was a stab at that.

What it does

Managing the personal data of members is just one example, but a powerful one. For one, most member based organisations just don’t know how to deal with this currently, trying to balance data protection laws, user experience and organisational flexibility. Unsuccessfully. They’re unsure who should be able to have access to what information, and how to give it to them, resulting in messy fudges, like excel spreadsheets being handed around to everyone, and leaders sending messages using their personal accounts.

It is also perhaps one of the core bits of infrastructure for a membership run organisation, the better this bit works, the easier it is to build on top of.

If you ignore all of the above writing, then put simply, this prototype is a CRM. Except it’s not, because we don’t have customers, we have members, so let’s call it an MRM. But by building it, I think we’re creating a founding block for organisations that simply aren’t possible currently, but are desperately needed.

The source code is on github, and I have an instance running on a free heroku plan, but I’ll provide screenshots and a walkthrough here.

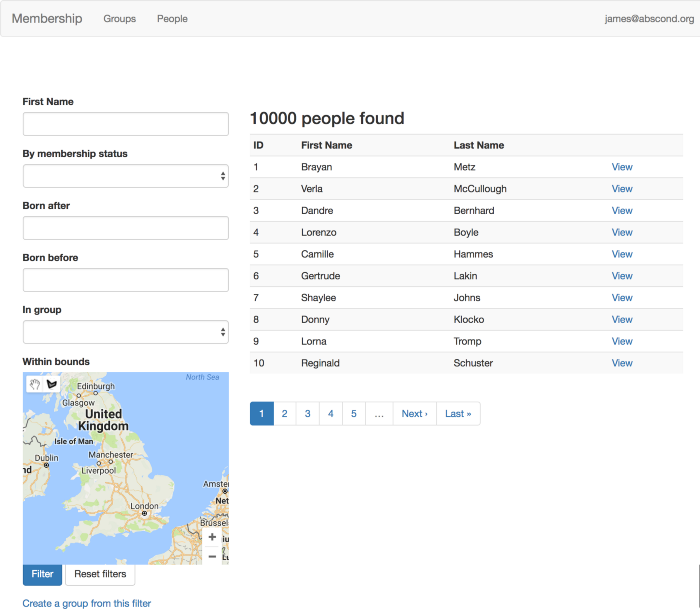

At it’s core, it’s a membership database. I have seeded it here with 10,000 fake profiles, but I also wrote an import script to be able to grab real data out of a nationbuilder account.

Already, a canonical list of members held in a database with open source code is a great leap forward for many membership organisations, but we need to make it usable.

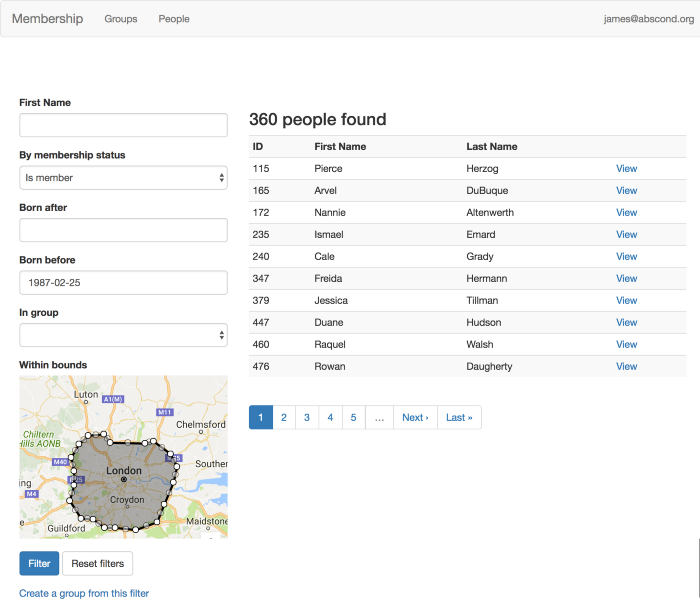

The most common task I’ve seen is being filtering and searching the members by various categories, and in this example I have created filters for membership status, date of birth, and physical address by drawing on a map. So if I want to be able to find all under-30s who live within the M25, I can do so like above.

A quick side note on why drawing on a map. Standardised geographic boundaries are complicated, not very user friendly, and often the data is not available. There has been some great work like MySociety’s MapIt to help developers access some of this data, and Democracy Club are campaigning to free more of it, but even then it’s a bit archaic and not all organisations necessarily map to these boundaries. So while we may use this data to seed these drawings, to avoid these problems and enable greater flexibility, nothing beats just drawing on a map.

So far so useful and many existing tools, to varying degrees of success, allow this to happen. But then how do you share this data? In practice, this is often exported as a spreadsheet and sent to an organiser of this group, to use in whatever tools they feel most comfortable with.

I want to cover two problems with this, the first and more obviously scary one is data protection. Personal data is now being handed around with very little oversight or guidance from the central organisation on how to use this data, leading to confusion around what is legal and what is not. This can be reduced by creating rules and procedures (again, it’s 2017) on who can access the data, and professionalising those people, but this starts creating brittle bureaucracy pushing us back into a more staff/customer relationship

But in my view, the even more fundamental problem is the member experience of this. We can not expect all members, especially new members, to fully understand the bureaucratic structures of the organisation they are a member of, but we needn’t make it more confusing than it needs to be. Being emailed from a personal email address by a person you have never heard of, representing a group that you don’t understand is confusing.

In every contact, the member should be able to have at least a basic understanding of who this person is, and how they fit into the larger picture of the organisation. They should be able to easily request to be more or less involved with this group.

As an example of this from Labour, when I was volunteering on the first Jeremy Corbyn leadership campaign, we had a moderately sized list of members who, by diligently following Labour Party policy, we were unable to contact to thank them for their donations because they had unsubscribed from Labour communications by entirely different groups about campaigns they didn’t know where happening. Another example being that when a member leaves a group, eg by moving house into another constituency, an increasingly common occurance, it can take a while, it it happens at all, for your personal data to be removed from that group’s silo’d member list.

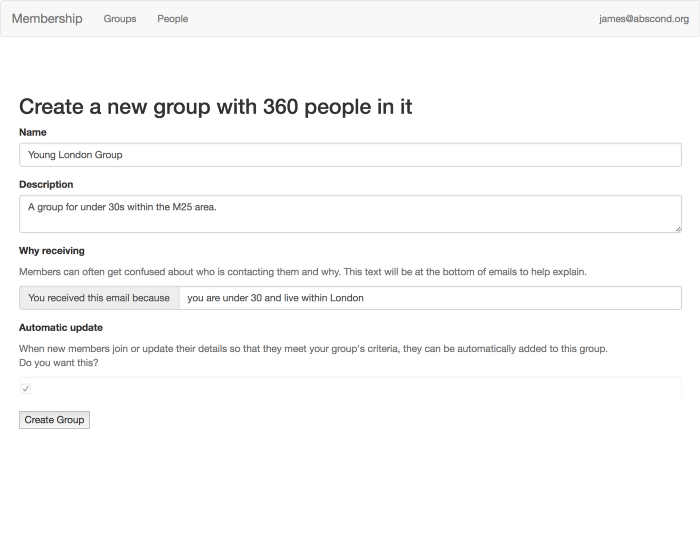

We can create tools that make all this easier if we start thinking about realistic semantics of these groups, and being able to represent this in databases and open source code. In my prototype, you can take any filter of members, and create a ‘group’ out of it. A group has many members (this is beginning to sound a bit like a first year computer science degree example), and we can programmatically and manually keep that list up to date. We can share that information with both the member, so they have knowledge of who has their information and why, and with an organiser, so that they can contact them with minimal bureaucracy.

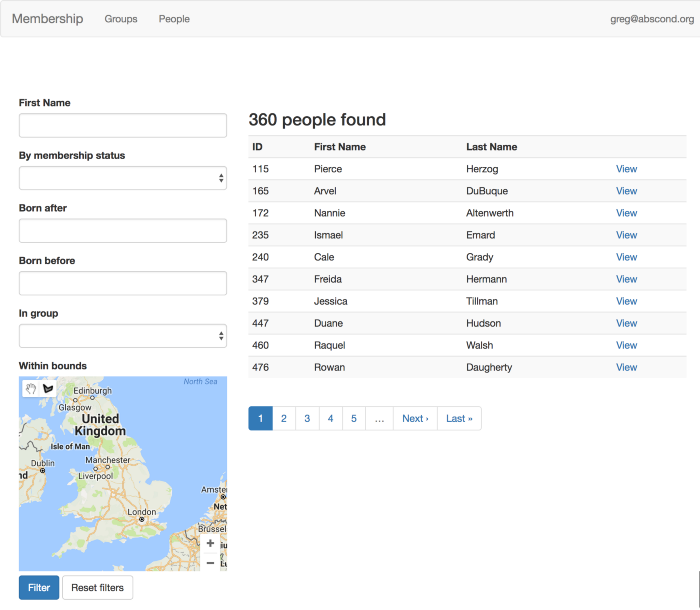

Here we have created a new logged in user, Greg, and he has been given privileges to the group we have just created. Note that he can only see the personal data of the members of his group, but he still has all the same tools as an admin. If he had appropriate privileges over multiple groups, all relevant members would be available. This information can be kept up to date by Greg, HQ, the user or an API, we can share with the member that Greg has access to their data and why he has it, and his privileges can be removed when necessary.

If we were following a good micro-application architecture, we might have a separate open source application to allow Greg to actually email members which gets the relevant data from this application via an API, but as this is a prototype and that’s probably a bit too nerdy to get into right now.

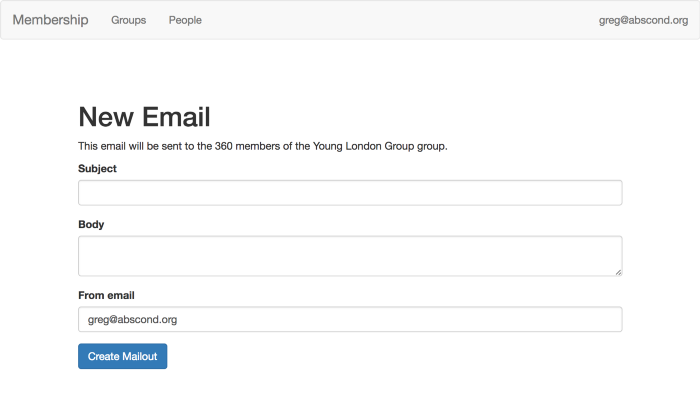

So I have quickly thrown in a minimal email client that uses Mailgun for delivery. This shows one functionally useful feature than can be built on such a structure. Emails sent from here can provide some clear explanation to members why they have received this email. The unsubscribe link can show the member all the groups they are a member of, providing some in context learning and navigation, while giving them more nuanced control over their involvement in the organisation as a whole.

What next

This is just a prototype, written alone over a weekend, and we probably shouldn’t be listening to yet another white man theorising alone in their house. I’m genuinely not sure what the next steps should be. I’m not sure if any existing large and established civic institutions are capable and willing to start genuinely exploring this stuff, and my own new charity is years aways from needing this sort of infrastructure.

But I’m hoping it shows some potential. By getting some of this core infrastructure right, we can build brilliant things on top of it and around it. For example, I think by getting it right, it unlocks the ability to build online democratic processes and tools to increase engagement of volunteers and the effectiveness of their engagement.

Entirely new things are also possible, like OAuth servers that allow members of one organisation to verify themselves to and share data with affiliated member organisations. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

I also hope, by writing this, that I begin to show the political power of organisational bureaucracy, and provide a practical example of how we need to be able to tweak the very core of our civic institutions to enable them to survive and flourish in the digital age. The importance of flourishing civic institutions hasn’t been as urgently apparent as it is now since the industrial revolution.

← Previous Post: Depression Next Post: Putting strings into databases and then taking them back out again →

For more content you can see all of my posts, or read about me.